"That's the Way it Was" (2 of 6): Surveying the Literature about Briercrest

ORAL HISTORIES OF 5 WOMEN FROM THE EARLY DAYS OF BRIERCREST (a paper presented at Research in Religious Studies Conference, Lethbridge, 2007) *

continued from Introduction

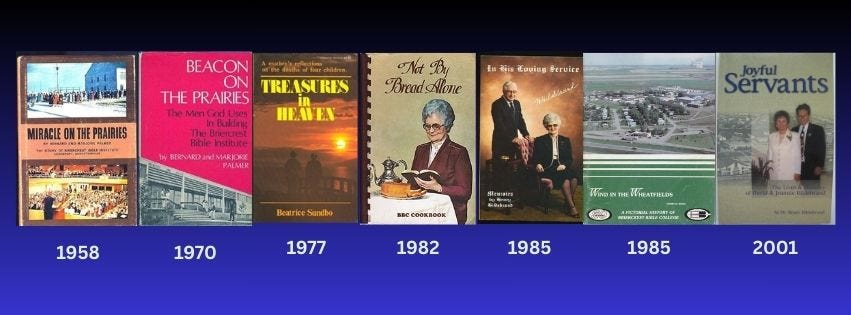

While much has been written on the history of Briercrest Bible Institute and the men involved in its founding, the stories and voices of their female co-laborers and wives have more rarely been heard. Regarding primary written sources, a significant amount of material has been published focusing on the founding and growth of Briercrest Bible Institute: Miracle on the Prairies and Beacon on the Prairies by Bernard and Marjorie Palmer, In His Loving Service by Henry Hildebrand, and Wind in the Wheatfields by Henry Budd. The emphasis in most of these books is on the roles played by men, with comparatively little attention given to the women who were involved in establishing the school. In fact, Beacon on the Prairies is subtitled The Men God Uses In Building The Briercrest Bible Institute. Bernard and Marjorie Palmer do have a chapter in Miracle on the Prairies titled “The Dean of Women Speaks,” Henry Hildebrand writes clearly of Annie (Copeland) Hillson [1] and dedicates two further chapters of his memoirs to women (chapter 8, “The Founding of a Bible School” and chapter 10, “Enter the Heroine,” about his wife), and Henry Budd’s pictorial history gives very fair coverage to women along with the men, in text as well as pictures. However, all of these books are written by men (Bernard Palmer with his wife) and focus on the institution, which was male-led with support staff comprised of some men, married or single, and many single women.

My interview participants noted that the school had an early policy of not employing married women, a significant factor in excluding women from institutional influence.[2] The primary sources lack narrative about the day-to-day lives of women behind the scenes, and what they do have is an idealized image of home life. According to Esther Edwards and Selma Penner, Henry Hildebrand’s wife Inger, “the Heroine,” was not necessarily typical and was so exemplary as to be intimidating for other women.[3] The ordinary experiences of married women have been largely overlooked.

One exception is Treasures in Heaven by Beatrice Sundbo. Here is the story of a wife (with her husband), who “saw four of her five children die.”[4] The Sundbo family began serving at BBI early after the school moved to Caronport[5] and this little book is full of names well known to those familiar with Briercrest history. Yet, Briercrest’s centrality is a coincidence of geography; this book is the memoir of one family’s grief, not a deliberately historical record about the Institute.

Another exception is Joyful Servants, a biography of David and Jeannie Hildebrand, written by David’s father, Henry Hildebrand. The account of David’s childhood documents mundane details such as colds, flues, earaches, and frequent visits to the hospital. There are also references to David’s mother and to Hildebrand family life[6] in the towns of Briercrest and Caronport. In this book, Henry Hildebrand is compiler as much as author, and many of the voices within are women’s. However, even though this book focuses on the people more than the institution, the writers recount memories of David and Jeannie, not their own narratives, and recollections prior to 1960 are few. These two elements place this book outside the parameters of this study.

Thus, a survey of primary sources available on the history of Briercrest reveals a significant and fairly obvious gap. It seems that it would be easy to fill this gap, but there is the problem of silence.

The Palmers write at the end of Miracle on the Prairies: “Who can say what has been done at Briercrest as a direct result of the silent, happy acceptance of the personal sacrifices made by the wives and families of staff members that serving at such an institution demands?”[7] If published literature were the only witness, there would be no argument. But, after interviews with only five women who lived and worked at Briercrest prior to 1960, it became apparent that the wives and families may have been silent, but not all were happy with or accepting of their situation. Jean Whittaker regrets the frequency of giving up her bed for visiting students and Bible teachers during her teens, and was shocked and frustrated to learn that the principal of the school was given a car when she could not get a desired bicycle.[8] Esther Edwards tells of how her children wanted a pony. Not being able to work for pay at Caronport,[9] she took a clerical job in Moose Jaw and [ironically] rented a school-owned car (for two dollars a day) to get there.[10]